On World-Making amid Contradiction and Crisis

Artist Suneil Sanzgiri breaks down the “insovereign” path to liberation.

by Suneil Sanzgiri

October 19, 2023

Suneil Sanzgiri is the fourth recipient of the UOVO Prize, which recognizes the work of emerging Brooklyn-based artists. Suneil Sanzgiri: Here the Earth Grows Gold, his first solo exhibition, is on view at the Brooklyn Museum from October 27, 2023, to May 5, 2024. The film, projection, and sculptural work on view present the concept of diaspora as a way to reconfigure our understanding of history and belonging.

In this essay, the artist, researcher, and filmmaker delves into the personal and global histories behind his projects.

When we were growing up, my father never discussed his childhood in Goa, India, in depth, or what life was like under the grip of Portuguese colonialism in the region, which lasted for more than 450 years. Born in 1942, my father witnessed both the independence and subsequent partition of India by the British and the eventual liberation of Goa from Portugal in 1961. That year would also see the assassination of the influential anti-colonial leader Patrice Lumumba at the hands of the CIA-backed Congolese army, marking a sizable shift in the landscape of violent counterinsurgency in the Global South.

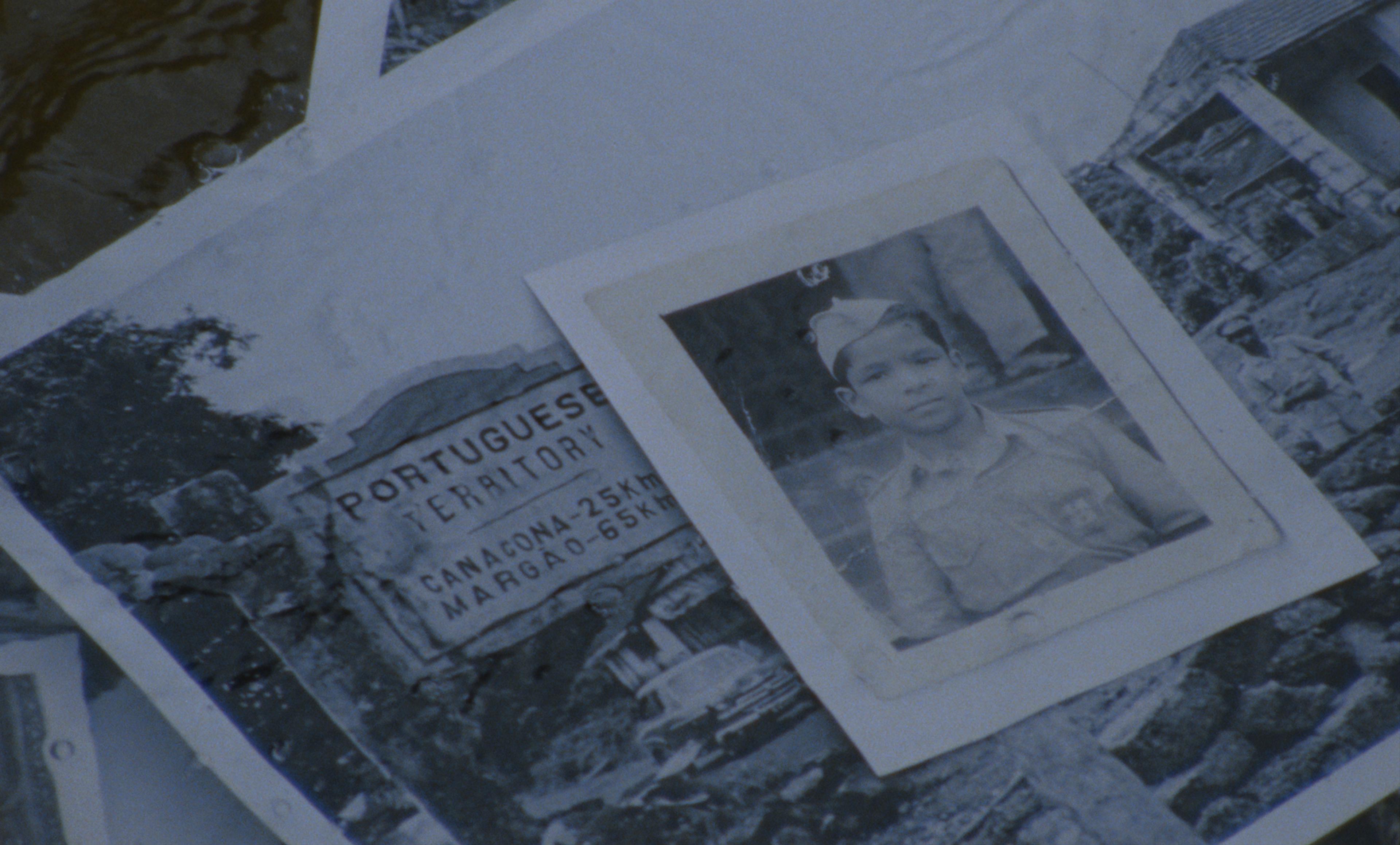

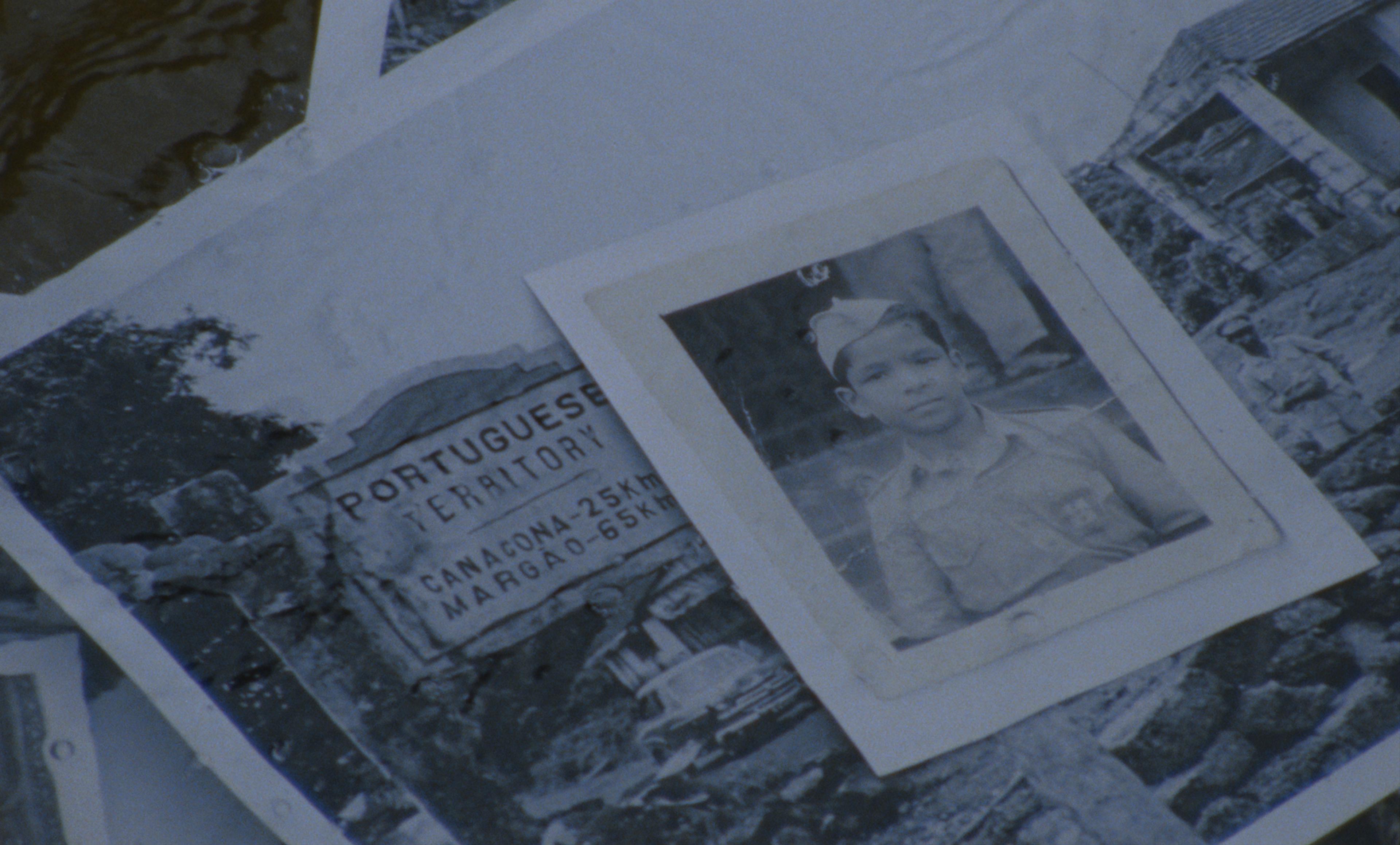

In 2017, on his 75th birthday, my father sat down with his three children and began narrating the story of his life. In that time, I started scanning my father’s photographs, coming upon images of him as a child in a Portuguese school uniform. In school, my father was given the option to learn either Portuguese or English, the former being the assumed rightful choice. Konkani, his native language, had been banned and outlawed in 1684. Documents, such as marriage certificates, were rejected in any language besides Portuguese. Nonetheless, Konkani was practiced discreetly, clandestinely, and after liberation in 1961, flourished freely once more.

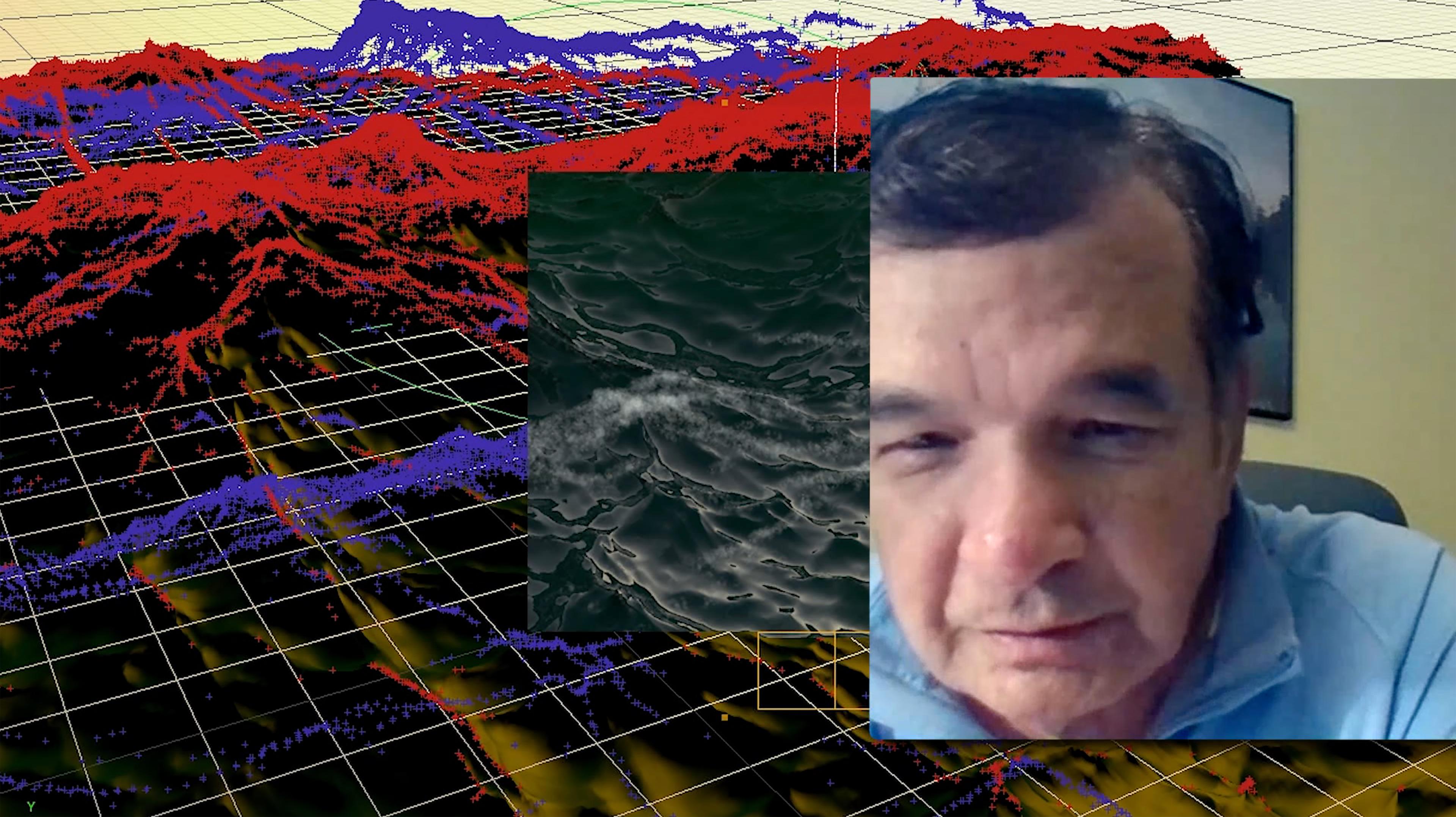

Attempting to learn more about the time leading up to Goa’s liberation, I began to interview my father via Zoom. He mentioned in one conversation that his mother’s family, the Sardesais, had been anti-colonial freedom fighters for generations. This passing comment would give an intimate clarity and weight to the films I wanted to make—films that challenged ideas around diaspora, ancestry, solidarity, and anti-colonial struggle and illuminated how technology and imagery can reframe our understanding of these questions across time and distance. Combining recordings of my interviews with my father with images from across Indian cinema, commissioned drone videography, 3D renderings, and 16 mm film, I attempted to tether and stitch together a tapestry that visualized the feeling of distance and desire, and how one could suture such a gap.

In those same interviews—which found their way into what would become the first part in my Barobar Jagtana trilogy, At Home But Not at Home (2019)—my father described scenes of Portuguese soldiers of Angolan and Mozambican origin deployed in Goa to maintain colonial order—another revelation. I had already begun reading more about a 1955 conference between African and Asian leaders known as Bandung—named after the place it was held in Indonesia—supposedly the first of its kind. These three intersecting points—my 2019 conversations with my father about our ancestors’ histories, his stories about a childhood under occupation, and the Bandung Conference of 1955—led to questions surrounding the presence of Africans in Goa and the presence of Goans in Africa. Questions became contradictions, contradictions became crises, crises became normalized. Struggle and image (struggle over representation, over self image, and over image of the nation), it seemed, bound these contradictions together. What mutual lines of struggle, companionship, if any, existed amid centuries of abject dispossession?

*

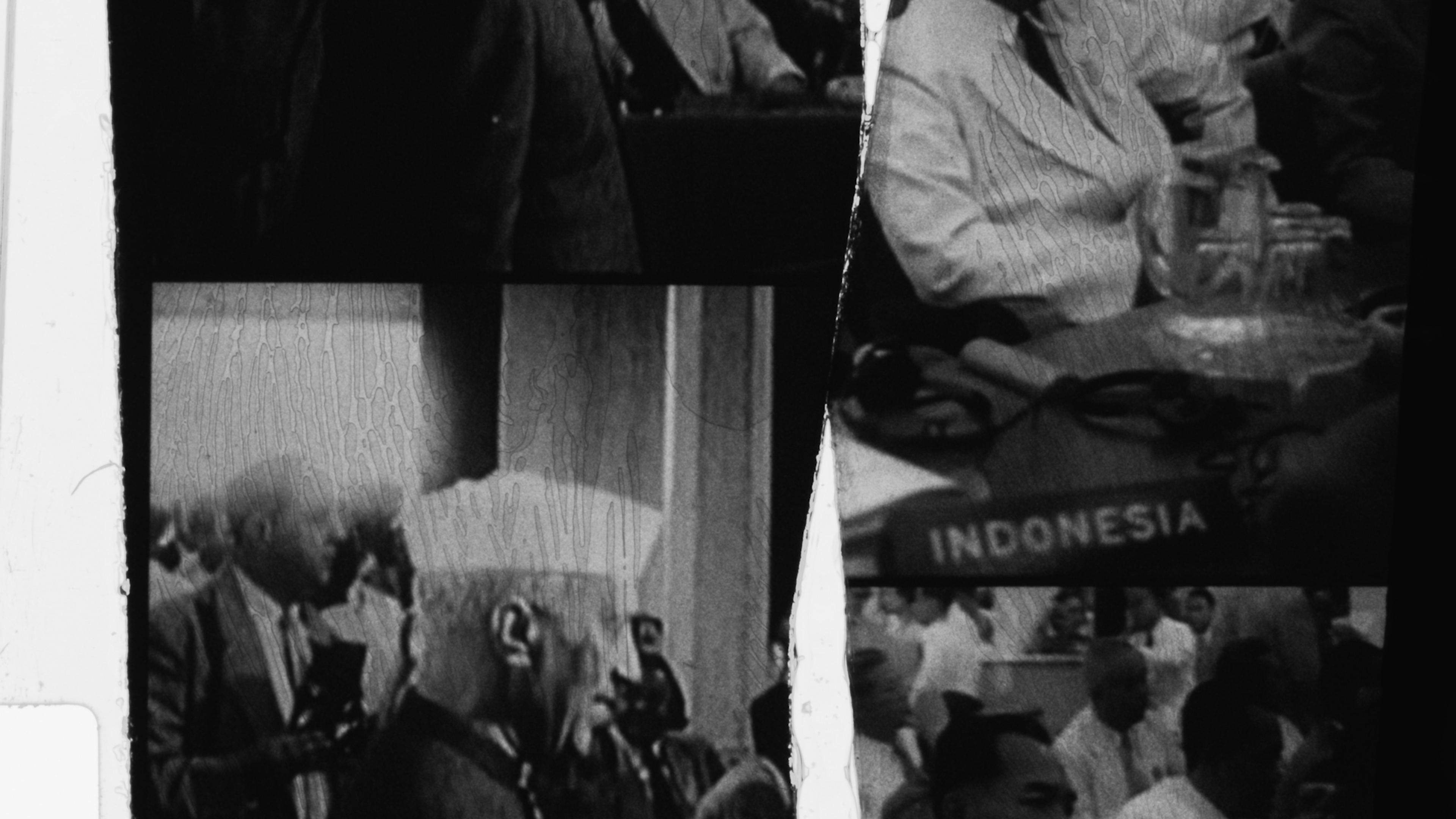

In April 1955, representatives from twenty-nine countries across Africa and Asia—representing over half the world’s population—gathered for a week in Bandung, Indonesia, to chart a new world freed from colonial domination and plunder, and to develop strategies of solidarity among the newly independent nations. The first large-scale meeting of anti-colonial leaders from the world’s two largest continents, the conference was immediately viewed with suspicion (and perhaps fear) by both the United States and Soviet Union. If those who had borne the brunt of the Western world’s ills began to unify, would they think of themselves as something more—more powerful, perhaps?

The Bandung Conference ended with nation leaders proclaiming a new declaration of human rights that reaffirmed commitments to each other’s sovereignty and rejected all forms of colonialism and imperialism, past and present.

Or so the story goes. “Solidarity among postcolonial nations was performed well in Bandung, but it was ephemeral,” notes scholar Shirin M. Rai. “This conference was a bid by the newly independent nation-states to perform on a world stage—to create a space between the two super-powers [the United States and Soviet Union] that were crowding out the voices of those who spoke differently.”

“Performance” is an apt term, as the so-called anti-colonial “spirit of Bandung” recoiled in the wake of the twentieth century’s whiplashing contradictions. Many people—artists, writers, poets, academics—have attempted to grapple with what happened during this time (the political and ideological differences among vastly different regions and peoples, the absences of certain figures and countries, and the internal tensions and rivalries among those present) and what came after (the developmental “modernizing” by newly independent nations to play “catch-up” with the West, and the crushing imposition of new forms of imperialist and colonial dominance under neoliberal capitalism).

What does it mean to make a world out of a world never made for you?

However, more pressing than the question of performance at Bandung is the question of narrative. To be sure, there is no one way to narrate these histories, nor should there be—as narratives so often betray those they describe—nor would history find justice at the end of its fishing line.

Jamaican writer David Scott argues in Conscripts of Modernity (2004) that history does not move through narrative, nor through linear notions of progress or justice, and that the worlds once envisioned by radical anti-colonial figures in the past are not the worlds that we have come to inhabit today. “Faced as we are with the virtual dead end of the Bandung project . . . this story is an exhausted one.”

However, Scott does not discount the possibility of hedging a way forward. Scott writes, “If the longing for anticolonial revolution . . . is not one that we can inhabit today, then it may be part of our task to . . . begin another work of reimagining other futures for us to long for, for us to anticipate.” Colonialism is certainly not over, nor are its effects beyond the scale of living memory. It is ongoing, as are the many struggles against it. As critical histories of the transatlantic slave trade and genocides of settler colonialism face daily censorship in the United States, and as authoritarian regimes worldwide seek to maintain religious “purity,” such as in India, the history that lives on in the popular memory of the people becomes the threat.

What, then, would it take for us to reimagine these “other futures”? Everywhere I looked, entanglements of the “Third World” found their way back to Bandung as the start to one thing, and the end of another. What if there are no beginnings, no endings, but instead glimpses, periodically, momentarily, of a continuum of mutual struggle that stretches across oceans, knows no borders, and has no allegiances?

And what if the nation-state was corrupt from its inception? Pointing to both the 1684 Peace of Westphalia (which led to the concept of sovereignty in Europe) and the 1884–85 Berlin Conference (which divided the African continent for European colonial powers), theorist and poet Fred Moten calls into question the concept of sovereignty and thus Third World nation-state building altogether. Is playing by Europe’s definitions and models such a noble pursuit?

Furthermore, questions of sovereignty and the state prompt questions of self-preservation. If the state must protect itself at all costs, whose sovereignty are we speaking of then and what (or who) constitutes the “insovereign”? To be “insovereign,” as Moten writes, is to seize a “radical discontinuity” with the past and present, forcing instead an interruptive presence, an “affective fugitivity.” Becoming insovereign, thus, requires a break with linear Western time. Averting the fixed goals of history and progress all together, the insovereign communes with the dead—and those not yet born.

While Bandung had been on my mind for quite some time, it was the life of Sita Valles that unnerved me, crystalizing the possibilities of radical kinship, solidarity, and revolutionary love on the one hand, and on the other bearing the brunt of unspeakable violence (and silence) in the aftermath of decolonization. She stood on the precipice between two worlds—one full of possibilities and beginnings, and the other foreclosed by greed, corruption, and Cold War paranoia.

The daughter of a Goan immigrant couple, Sita grew up in Angola with her two brothers. In 1968, Sita moved to Portugal to study medicine, where she was radicalized and became an active member of the Communist Party, along with her brother Edgar. She quickly rose to prominence in the party, known for her bright charisma and unwavering commitment to building a new and better world. After the Communist Party in Portugal helped to successfully overthrow the weakened dictatorship in 1974, Sita was invited to Angola to help with the struggling People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), where she met and fell in love with revolutionary José Van-Dúnem.

Angola gained independence in 1975 and almost immediately fell into a bloody, decades-long civil war with the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), which was backed by the CIA and apartheid-era South Africa. Poverty, hunger, and dire medical conditions plagued the newly formed nation as movement leaders dismissed the vocal concerns of the people and increasingly consolidated power. During this time, Sita made a name for herself in Angola tending to patients in rural areas. Increasingly disillusioned with the basic functioning of the MPLA, led by President Agostinho Neto, and their failure to satisfy the basic promises of the revolution, Sita, her husband José, and MPLA Interior Minister Nito Alves began openly criticizing the party. Fearing the rising popularity of the trio, Neto accused Sita, José, and Nito of fomenting a coup. What happened next depends on who you ask.

On May 27, 1977, Neto phoned Fidel Castro, who had played a pivotal role in Angola’s liberation just years earlier, to help put down the supposed coup in progress. Cuban forces stationed in Angola began working with the MPLA to systemically purge what would become a groundswell of dissent. Thousands of innocent people were killed that day, and over the course of the next few years, estimates of 30,000 more were disappeared. Sita, José, Nito, and many others were taken to prison, never to be heard from again. Some former officers claim Sita was executed by firing squad. Others say she was tortured and raped before being murdered in a ditch.

To this day, her remains, and the remains of thousands, have never been recovered. Despite an official apology from the MPLA (who remains in power), this era left such a traumatic mark on the public consciousness that discussions of these histories continue to leave people in fear for their lives. “Disappearance is a complex system of repression, a thing in itself,” writes sociologist Avery Gordon. “With less noise than expected, it removes people—including and significantly those it never tortures or kills—from their familiar world, with all its small joys and pains, and transports them to an unfamiliar place where certain principles of social reality are absent.”

Sita’s life—a life of utmost bravery, dedication, and revolutionary love for all people—ended as her hopes for better futures did: covered up, falsified, and with irretrievable remains. Perhaps this is what drew me most to Sita: the stark contrast between her life and her death, her dedication to the people of Angola and her death at the hands of the people she’d helped put in power. “They are the ones whom the state can put to death in the interest of its self-preservation without any explanation,” Moten writes about the insovereign. Could Sita’s life be understood through such a rubric? Sita’s life of affectability—her infectious transmission of desires, from one person to the next, for all mankind’s liberation—marked her for obliteration. “They [the insovereign] are the ones who are in passage, not just from this world to the next but from world to earth, world to ground or underground; world to water or underwater.”

*

For many nations, life after independence was subject to the same essential contradictions as before. Civil wars, corruption and greed, and religious strife can all be tied back to colonial retribution, revenge, and maintenance of “the abyssal line”—the line that separates the world along the axis of those deemed human and those considered less than human.

As colonizers were expelled from many parts of the world, some would even burn down their own plantations, rendering the land unusable for the native populations. Opportunists, who often resembled those overthrowing their colonizers, swept in to take quick control over popular industries—predominantly those related to tourism or the extraction of natural resources. They would also become accomplices to predatory regimes of debt that ensured the continued flow of capital, labor, and resources from the Global South to the North.

Yet multiple things can be true at once: that the so-called “post-colonial” societies were plagued by corruption, greed, and power vacuums, and at the same time were forced to fend off violent, protracted wars (either directly or by proxy) from the juggernaut of military power wielded by the United States and its capitalist servants in the Global North.

Today, as India’s open genocide against its Muslim population increases by the day, the so-called world’s largest democracy has been razed by a bulldozer. Rooted in histories of Partition—one of the world’s greatest tragedies, in which more than one million people died and some twenty million were displaced as the Indian subcontinent was carved up into India and Pakistan—Hindutva, India’s Hindu supremacist ideology, is ripping apart the country’s constitution. The question of whether Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, ever lived up to his promises of a secular India remains on the table.

*

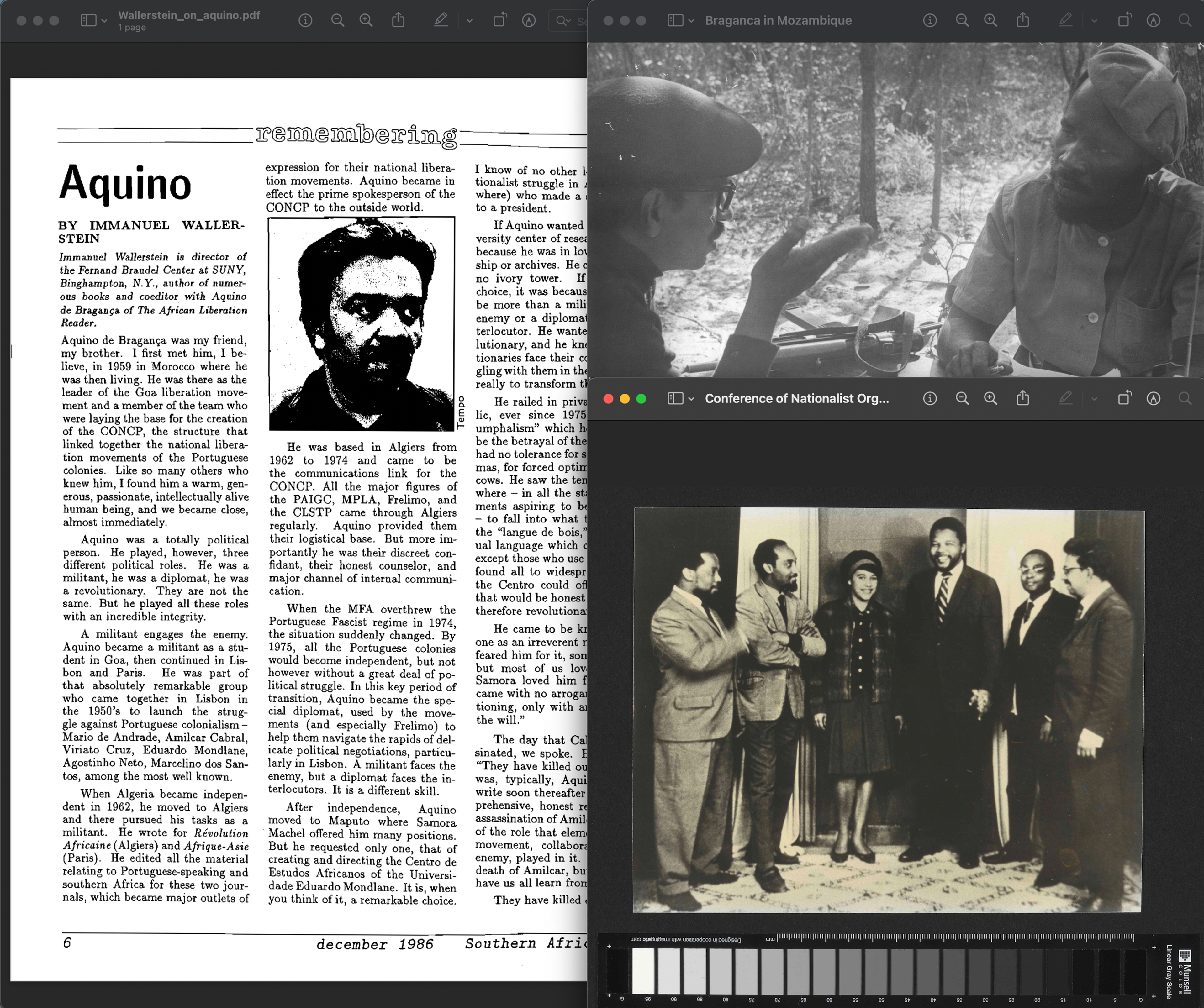

While Bandung was not the first, nor the last, conference to champion intercontinental world-building and coalitions of “the darker nations,” it left an indelible mark on the anti-colonial imagination. In 1961 alone, two major Afro-Asian conferences occurred. In April, the first Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP) took place in Casablanca, Morocco, and in September the First Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement was held in Belgrade, Yugoslavia—the latter perhaps representing the Bandung Conference’s most defining legacy. The CONCP featured leaders of the liberation movements in Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Angola, Sao Tomé & Príncipe, and Goa. Notable participants included poet Mário Pinto de Andrade, husband of filmmaker Sarah Maldoror and cowriter of her 1972 film Sambizanga, and Aquino de Bragança, a Goan physicist, journalist, and anti-colonial leader and frequent comrade of everyone from Amilcar Cabral and Frantz Fanon to Julius Nyerere and Samora Machel.

Acknowledging that no history, no narrative, is ever complete, possibilities are glimpsed and grasped, continuously, simultaneously, through the past and the present combined.

At the end of 1961, Goa would be liberated. Pressure from African freedom leaders for Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to intervene in Goa helped turn the tide in the centuries-long struggle against the Portuguese empire. In this sense, Goans owe much to the leaders of Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau for our liberation. Though solidarity is not—nor should it be—transactional, nor conditional, one might ask: what have we done for them?

To engage in the question of Bandung, or Afro-Asianism, is to find ourselves mired in seemingly incompatible realities, paradoxes, and controversies. How is it that solidarity amongst the so-called “global majority” couldn’t feel further from view? Anti-Blackness runs deep in South Asian communities, as it does across the world. Proximity to whiteness and illusions of power have been ingrained in South Asian communities for centuries due to the compounding ills of colonialism, colorism, and casteism—the last being an issue that continues to violently plague the subcontinent daily through horrors beyond description. During colonial rule, Indians were often exported to other countries not only as expendable laborers, but also as middle managers. Goans, for example, frequently assumed roles as administrative and civil servants of the Portuguese, contributing to the exploitation and oppression of the Black population of the African colonies. This tension would lead to Goans (and many Indians around Africa) often being expelled during the anti-colonial revolutions of the twentieth century, and in some cases, like in Uganda, expelled violently.

This, in a very real sense, is when crisis becomes contradiction and when contradiction enables crisis. Recognizing the potential of this terrifying split in these already torn peoples, Pia Gama Pinto, a Kenya-born journalist of Goan origin, fought alongside the Mau Mau and Jomo Kenyatta—the nationalist leader who would become Kenya’s first prime minister—against the British. Gama Pinto developed a close friendship with Malcom X upon the latter’s visit to Kenya; both would later die by assassination, only days apart from each other. Gama Pinto is now considered by many Kenyans as their first political martyr after independence.

What then does it mean to make a world out of a world never made for you? Two remarkable examples are the anti-caste Dalit Panthers Party, inspired in the 1970s by the Black Panthers, and the correspondence between W. E. B. Du Bois and the radical anti-caste revolutionary and cofounder of the Indian constitution B. R. Ambedkar. Another is the struggles in the United States for Black liberation and against the continued violence against Asians—all against the backdrop of a complex history of solidarity, or the lack thereof, between Black and Asian communities.

What began as an attempt to find traces of connection between Africans and Indians, rooted in my father’s childhood observations of African soldiers in Portuguese uniforms reluctantly stationed in Goa, continues to inform my search for these histories. Acknowledging that no history, no narrative, is ever complete, possibilities are glimpsed and grasped, continuously, simultaneously, through the past and the present combined.

We must propel ourselves into these complexities and paradoxes—for what else is solidarity but an intricate mess of possibility? Perhaps, even if under threat of annihilation, it is the insovereign who can show us the way, with the strength of their desire to build worlds and break down others, a desire so strong that no regime may claim it as their own. This is the world of the insovereign, a world still yet for us to build.

Suneil Sanzgiri (born Dallas, Texas, 1989; active in Brooklyn, New York) is an artist, researcher, and filmmaker.