How Jamel Shabazz Photographed the “Heartbeat of Brooklyn”

“I remember, vividly, telling them, ‘I have to get this photograph. I can tell you two really love each other.’”

by Corinne Segal

May 31, 2023

For decades, you’ve seen him around: walking down Flatbush, up Church Avenue, or in the open expanse of Prospect Park, photographing best friends, devoted fathers, the stoops of Brooklyn, and the ebb and flow of people on the streets. Jamel Shabazz returned to New York in 1980 from his time serving in the military with the resolve to capture it all; since then, he has produced an extensive body of work spotlighting the brief, intense connections that make up New York City life.

In the process, incidentally, he also became the confidant of hundreds of his subjects, for whom their portraits would become evidence of a much longer conversation. He counseled young people through heartbreak; he observed quiet moments of community between strangers; he drew out the playfulness between friends and the steadiness of lovers. Now, he wonders if any of them will find him again.

Shabazz reflected on his years of chronicling New York City life through the stories of 10 photographs, most of which are on view this summer on the Brooklyn Museum plaza. Hear from him below or visit Jamel Shabazz: Faces and Places, 1980–2023, on view through September 2023.

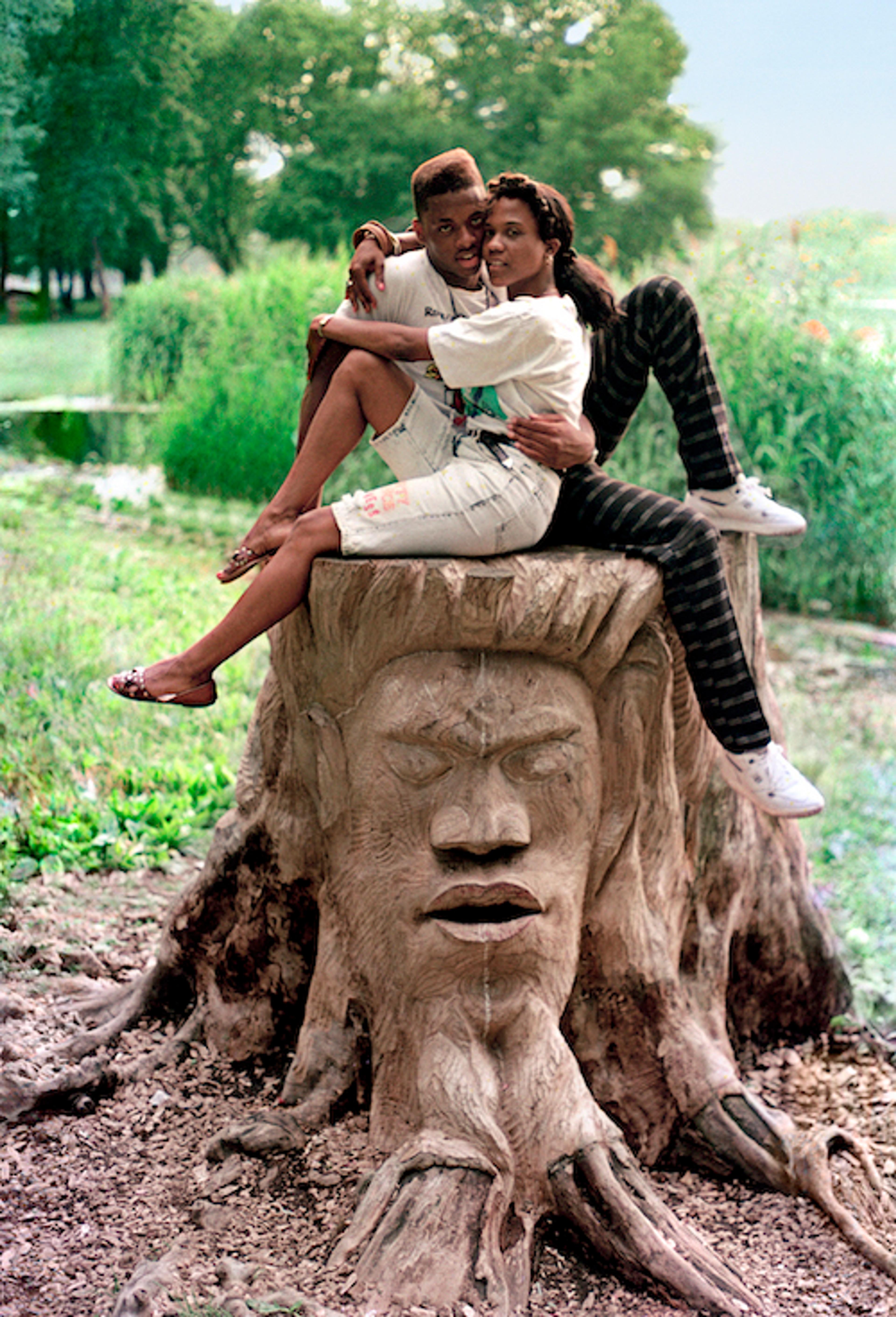

The Art of Love

I remember entering the park and seeing them from afar. I immediately started rushing to get to them as soon as I could, because I did not want them to move. I saw love, I saw artwork, and it was just a really unique moment. Both of them were dressed very stylish, and I had to get the photograph. I remember, vividly, telling them, I have to get this photograph. I can tell you two really love each other.

The person who created the carving in the tree was a very renowned Brooklyn artist who would do that throughout Prospect Park. Those carvings were all over the place, but the Parks Department destroyed all of them. I would use them as a backdrop to a number of my photographs for a couple years.

I know what love feels like, what it looks like. I knew it was there. I knew that was a very special moment for them and they wanted to be recognized—they’re sitting on that tree like it's a throne. I love to approach couples that love each other and I let them know, I'm approaching you because I can see that you really love each other. I remember her saying, I do love him. I want them to know that I recognize it, and I wish the very best for them. And I always tell couples that when I photograph them.

Unfortunately that couple never called me, you know, but I'm glad I do have the moment. I do believe that they're going to reach out to me one day.

Reflection of a Father

This photograph was taken outside the Albee Square Mall, which was a very popular location that I would go to capture images. On this particular day, that young man was out there with his son, just enjoying the scene. One of the reasons that it was very important for me to document fathers, as fathers are oftentimes viewed as being absent. I wanted to dedicate some of my time to celebrating them in every capacity, and I just felt that this image would be a really important part of the conversation from a different perspective. In a lot of my photographs and just in general, I like people to pose, but this one just came to me naturally. It was as if it was waiting for me to take it. I observed it and just froze that moment in time.

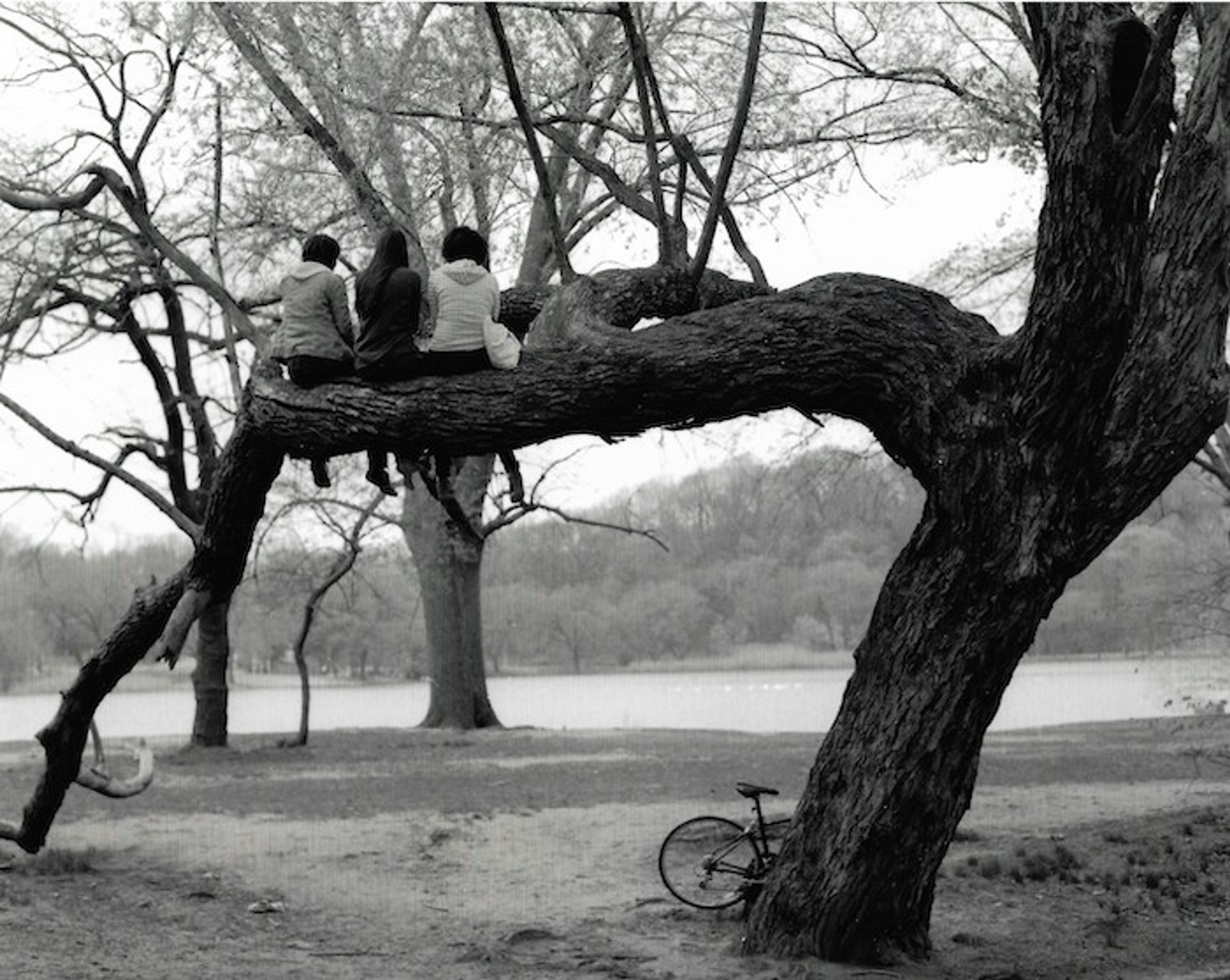

Best Friends

I happened to be walking in Prospect Park one day, and saw these women sitting in this tree. I had two cameras with me; my black-and-white film camera and my digital camera. I crept up and froze that particular moment. One of them turned around and saw me, which was great, because she was able to engage me in conversation about why they were sitting on this particular tree. What she shared is that they were best friends having gone to grade school together and now as college-aged women had made it an annual ritual to meet up at that tree. When Hurricane Irene came along in 2011, it took down the tree. So for me, that picture has even greater meaning now, not only to me, but I could imagine to them as well.

A Frozen Moment in Time

Prospect Park along with Central Park are two of my favorite places in the city. Over the past 40 years I have spent a substantial amount of quality time in both locations, probably a little more time in Prospect Park due to the close proximity. Since my early days as a young child coming of age, my father would often take me to Prospect Park. He too was a photographer, so I grew up looking at images from there, developing a great appreciation for it. When I first came home from the military and was seeking to develop my skills as a photographer, I would go to these parks focusing on everything from sunsets, sunrises, and ordinary people that I found interesting. Spending time in the park afforded me a temporary escape from the fast pace of city life. Photographing in those two ideal spaces also provided me with the opportunity to create various distinguished bodies of work, from environmental portraits, candid images of families, and endless celebrations that took place on any given day. The above photograph was a serendipitous moment. I was taking a casual stroll in the park on a beautiful fall day and came upon a young man photographing the couple posing. Having my camera out and at the ready, I snapped this one shot and froze the moment in time and I consider it to be one of my prized photographs.

I came from both the Red Hook and Flatbush sections of Brooklyn, so I mainly documented African American and Caribbean culture. But when I went to Prospect Park, I was able to travel throughout the over 500-acre area and document so many different cultures and communities, helping me to broaden my body of work.

“It was beyond the photograph. The photograph actually became evidence of the conversation.”

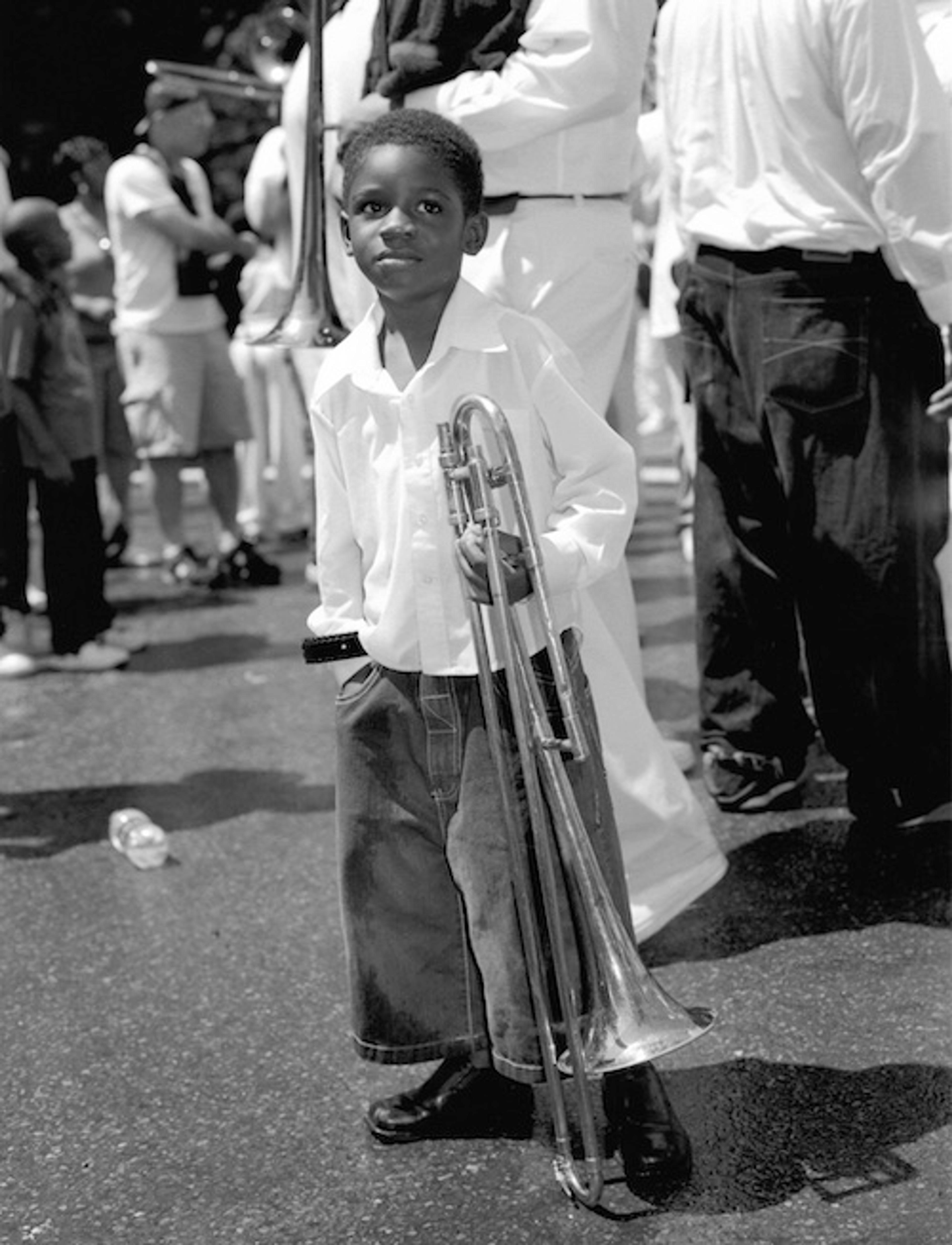

Young Visionary

This was at an event in Harlem; a celebration of a renowned activist. His name was "Sweet Daddy" Grace, and there was a celebration for him every year in Harlem, with an open invitation for baptism. There would be hundreds of people out there and I happened to see this young boy who looked like he was in deep thought. Something about him was very intense, and I was a little apprehensive about taking his photo in the beginning, because I wanted to ask him or ask an adult, but I just took a chance and thought, let me just capture this moment before it leaves me. It was one of my most recent images and was taken around 2015, which is somewhat recent to me. And it is very important to me, because of the light, the composition, the expression on the young boy's face, and the determination in his eyes. It is very important for me to photograph children in a dignified way.

The event was very celebratory and it was a very noisy atmosphere, but he was in another zone and was looking outward. To me it seemed like he was wondering, “What type of future am I going to have?” Albeit, the ceremony was religious, and he was around all of these elders; there were no other young people there. He was somewhat out of place and it seemed almost like he might have been conflicted, like, “I'm here with these adults, and I might want to be with my friends, but I have to be here.” It was like he was standing at the crossroads of one's life, one's journey. I am really curious about where he is today and to question him, about what he was feeling at the time; what was he going through?

Major General Hawkins

I took this at the Veterans Day Parade. I felt that it was very important not only to photograph veterans, but to document high-ranking African American veterans to show their contributions to protecting America and to capture their dignity. Sadly, two years after that photograph was taken, this gentleman passed away.

I come from a family of veterans. My father was a Navy veteran who served in the 1950s, as a photographer. My grandfather and all of his brothers were veterans as well. I also grew up in a veteran community. Every Memorial Day, they would get together and speak about their experience in the service.

I went in at the age of 17 and I had an opportunity to leave the country and go to Germany, which was a really profound experience for me. It was my first time being out of the country. While I was over there, I would think about New York all the time, especially when I would be out in the field on guard duty. I purchased a camera during my time over there, and once my time was complete, during the summer of 1980, I came home with the determination to never be without memory. I came back to New York, and my father put me under his wing and started teaching me. I went out to document everything that I missed when I was in Germany, from the buses, the trains, the people, the love, everything. I was like a kid in a candy store. Everything was so fresh to me. I came home with the determination to just document my life.

One of the greatest gifts that my father gave me was the idea of carrying your camera everywhere you go and documenting everything, from the streets to the subways. And that's what I did. The camera became like a compass to me.

Sisterly Love

That picture was taken in Prospect Park around the 1990s. I met them at Jones Beach. So many men wanted to photograph them—they were very attractive. They knew that I was a professional photographer, and I asked them if they would walk me to another area to get away from all the people. I had to really do some maneuvering because [the men] were following me. One of them even took out a notebook and he wanted to know, What did I say to them?

I wasn't really satisfied with pictures from the beach. I felt that I wanted to document them in a more dignified way. So that's when I told them, if we can connect in Prospect Park and you dress well, with shoes on, I can create something very refined.

When you approach two best friends, whether they’re male or female, old or young, and you let them know, look, the reason why I want to photograph you is because I can tell you two are really close and you really love each other—that makes it a lot easier. That opens them up, you know? It’s important to me to just show that love, that connection.

Black in America

It was the day of the West Indian Day parade, and as I was walking around Eastern Parkway—I believe at President Street—I happened to see this young man on the steps. And I just immediately knew that was an important photograph. It became a part of the series I was working on based on the American flag. I was greatly inspired by a book by photographer Leonard Freed called Black in White America. So when I saw that image, I immediately thought of that book and what this image meant.

Early on, when I looked at my father's photographs and my grandfather's images—which came from Crown Heights, a lot of them—the steps were always in the background. And as I started to develop as a photographer, I studied the work of James Van Der Zee, the great Harlem photographer who documented the Harlem Renaissance, and he used the steps as a backdrop as well.

So I started another project called “Home Front.” It was a series and it was based on the ideas of James Van Izzy, using the steps as a backdrop to create environmental portraits. I found that in walking both in Harlem and in Brooklyn, I would find so many people sitting on the steps. Unlike the streets, where people are in motion, with people on the steps, I have a greater opportunity to take a moment and engage them. Throughout all the different cities I would go to, I would travel and I would look for people sitting on the steps. It was a very important body of work of mine.

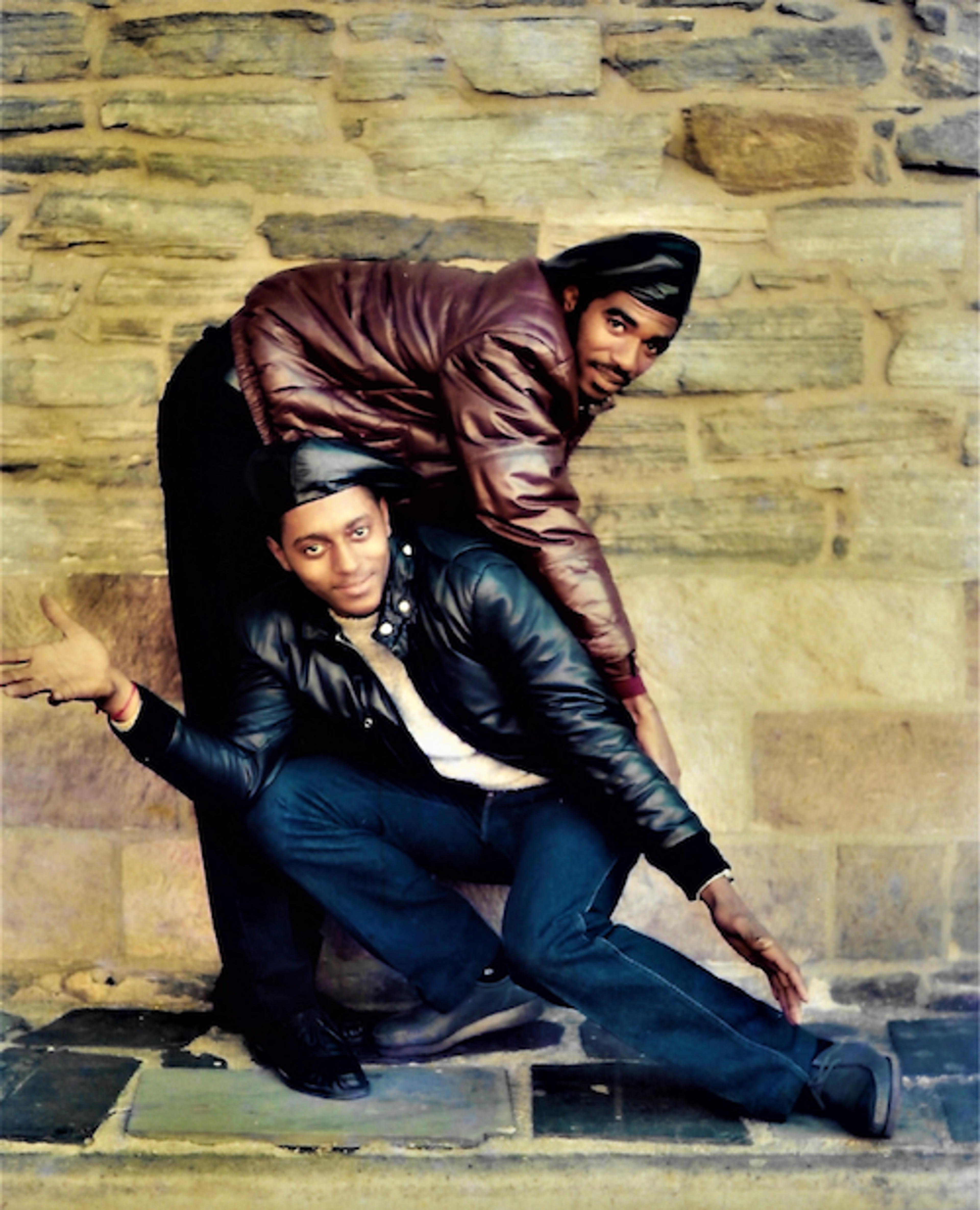

Style and Finesse

You had certain characters in the neighborhood [for whom] posing became this art form. It's a form of self-expression. These guys, they would dress very debonair. They gave me this very unique pose that I've never seen anyone ever mirror before. Here you have two young men who are very comfortable within themselves, and that makes it special.

I don't really think I can get a picture like that today. It was just a very different time, when there was still the sense of hope. As time started to shift, my images, the gaze, started to look very different because now with the crack epidemic, a lot of people were being impacted both directly and indirectly. There was a lot of death and destruction and addiction. There was a lot of loss. When I fast forward to today, it's a whole different time. Now I'm very apprehensive to approach people. I find, today, with a lot of young people, there's a lot of anger. I'm still able to bring out an element of joy, but it's not as frequent as it once was.

Even as I revisit my negatives, my scans, it's very emotional to me because I'm rediscovering so many photographs of people who are not here. So it hits me hard, you know. There's a lot of triggers, always. There's not a moment that goes by where there's not a trigger. That's why I have to be very selective in showing images when I do presentations, because I will get caught in the moment and I go into a really deep zone trying to explain what's happening here, because it’s deeper than what anyone could ever imagine. A lot of my peers, they haven't really shared similar thoughts because a lot of them are younger than me and they haven't had that experience to witness as much

A Time of Innocence

I just rediscovered this photograph after over 35 years of scanning negatives and I had absolutely no memory of it. It blew me away. I might have taken it around 1982, when I was 22 years old. It was taken on Flatbush Avenue.

Flatbush was one of the greatest locations to document people. I found a really great location at Church Avenue and Flatbush, where there's an old Dutch church that’s been around since the 1700s, and it has a very beautiful brick wall that’s in a number of my photographs. I would just work my way from one point to another point to document all the various people. And as time progressed, I knew people so they would just invite me to photograph them and their new friends. It was never a dull moment. There was always something going on in the avenue. Flatbush and Church was that nucleus—it was that major conduit, that heartbeat of Brooklyn, that particular area of Brooklyn that so many people came to who I knew from both Flatbush, East Flatbush, Brownsville—for whatever reason, a lot of people traveled up Church Avenue.

Beyond the photograph, it was about creating conversations with people. I was very concerned with a lot of things going on. We had the AIDS epidemic, the crack epidemic followed, and I was concerned with young people dying. I was trying to engage them in conversations about their goals and objectives—even my time in the military, and how they might consider going in as a career option. I was trying to save lives. I saw the beauty in a lot of young people, and I knew that there were dark days ahead, and I was just trying to be a big brother to a lot of the young. It was beyond the photograph. The photograph actually became evidence of the conversation.

Corinne Segal is Senior Manager of Web Content at the Brooklyn Museum.