The Brooklyn Museum Announces Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens

On View October 10, 2025–March 8, 2026

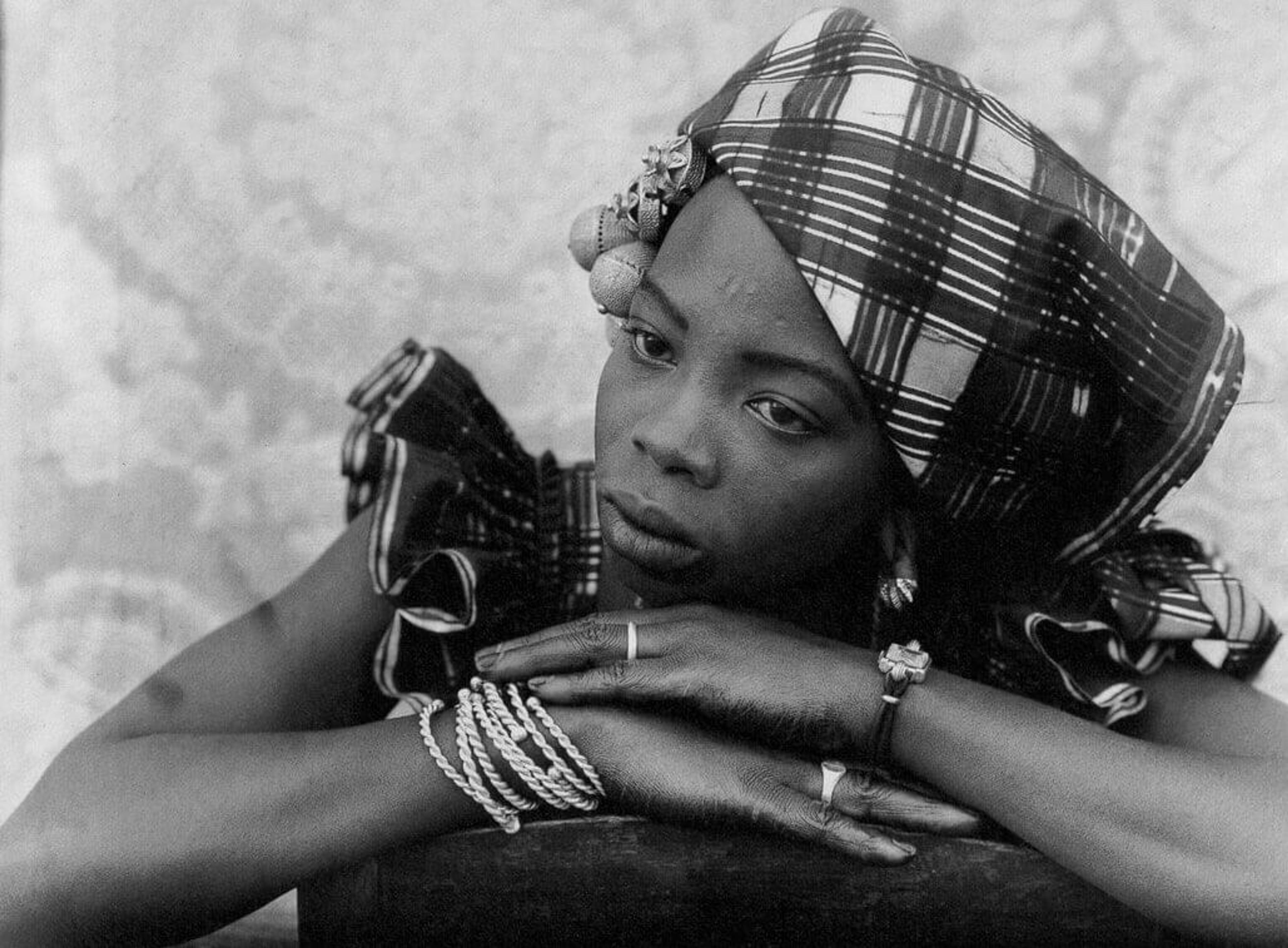

The exhibition Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens honors the artistry and legacy of Seydou Keïta (Malian, ca. 1921–2001), who documented a critical chapter in West African history—one of immense hope, politically and socially—in a period defined by a rapidly expanding modern world and a new sense of Bamakois identity. The show features nearly 275 works, including renowned portraits, rare images, and never-before-seen negatives as well as textiles, jewelry, dresses, and personal items that fully immerse visitors in Keïta’s rich photographic landscape. Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens is organized by guest curator Catherine E. McKinley with Imani Williford, Curatorial Assistant, Photography, Fashion, and Material Culture, Brooklyn Museum.

Keïta was born around 1921 to a Malinke family in Bamako-Coura, or New Bamako, a growing colonial commercial center within the historic Malian city. His childhood saw emerging liberation struggles across the continent and growing expressions of modernism as Bamako served as the capital of French Soudan and subsequently the newly independent Mali in 1960.

Keïta documented Malian society in the late 1940s to early 1960s, an era of transformation and aspirations for independent statehood. A master at lighting and composition, Keïta has a unique ability to capture the tactile qualities of his sitters—from their fashion and choice of accessories to the personality and self-presentation they put forward. In collaboration with his subjects, he sculpted their poses, clothing, and style, forming monuments to their selfhood. When they first reached Western viewers in the early 1990s, his images drew unprecedented attention in the worlds of art, music, fashion, design, and popular media, forever changing the global cultural landscape. Today, these bold and engaging portraits continue to invite viewers into direct dialogue with Keita’s sitters.

Largely self-taught, Keïta first received a camera as a gift from his uncle at age 14. In 1935, he became an apprentice to his mentor, Mountaga Dembélé (1919–2004), Mali’s first professional photographer to earn a living with his studio. From there, Keïta opened his own studio in 1948 in front of his family home in Bamako-Coura, becoming Mali’s second photographer. The studio became a destination for people from all levels of Malian society, welcoming not just the elite citizens of Bamako but also remote villagers, international travelers, and those passing through on the Dakar-Niger railroad. Keïta’s work is notable for capturing how the people in his studio saw themselves, allowing for a playful self-expression backgrounded by increasing political tensions and rapid evolutions in the government. His studio offered props, including European and Malian clothing, motorbikes, Western watches, and novelties.Through the years, Keïta developed his very own style of portrait photography and a new type of modernist expression.

This period lasted until 1963, when Keïta was enlisted to work for the newly independent Socialist Republic of Mali. Forced to relinquish his studio, he documented state affairs and performed forensics for increasingly punitive governments until 1968 when he retired to work in camera and automotive repairs. In May 1991, the exhibition Africa Explores: Twentieth Century African Arts opened at the Center for African Arts in New York, where Keïta first debuted to Western audiences. In 1994, the Fondation Cartier in Paris presented Keïta’s first solo exhibition, which rocked the art and photography world, cementing him as the premiere African studio photographer of the twentieth century. The exhibition positioned Keïta as a peer of noted photographers such as Irving Penn, August Sander, and Richard Avedon, his contemporaries in portrait photography, and created enormous interest in Keïta’s work.

“Thirty-four years since Keïta was first introduced to American audiences we have an opportunity to view new discoveries in his work and understand just how singular he was, practicing at one of the most pivotal moments in African and world history. He had an extraordinary artist’s ability to render the tactile. We can visually ‘finger the grain’ of the sitter’s lives and better understand them beyond just their relationship to studio photography or documentary,” says Catherine E. McKinley, guest curator, author of The African Lookbook, and director of The McKinley Collection.

“It is very exciting and deeply moving to rediscover Keïta’s work and to feel the presence of his sitters—some of whom we meet here for the very first time—thanks to Catherine E. McKinley’s thoughtful research,” says Pauline Vermare, Phillip and Edith Leonian Curator of Photography. “We hope visitors feel the wonder and possibility that Keïta’s studio represented for so many people.”

A Tactile Lens brings together a remarkable range of Keïta’s photographs, which demonstrate the breadth of his oeuvre and the splendor of his artistry. Thanks to a generous loan from the Keïta family, an extraordinary group of never-before-published works has been preserved and imaged by the Museum on the occasion of the exhibition. A selection of the portraits will be displayed—on lightboxes and as a projection—for the first time. In addition, an array of vintage prints, many made by Keïta himself, and some of which are hand-painted, offer renewed emphasis on the photographic object itself. Rounding out the selection are larger prints made later in Keïta’s life, or posthumously, which feature the distinctive black-and-white tonalities that Keïta came to be known for. Joining the photographs is an immersive installation of personal belongings, textiles, garments, and jewelry that can be seen in Keïta’s portraits. Together, these objects highlight the self-invention, search for identity, and syncretism of Mali that Keïta’s sitters sought in the mid-twentieth century.

A fully illustrated catalogue will accompany the exhibition, featuring a new biographical essay by Catherine E. McKinley based on extensive interviews with his heirs and from leading art professionals and historians such as Jennifer Bajorek, Duncan Clarke, Howard W. French, Sana Ginwalla, Awa Konate, and Drew Sawyer, offering new insights into the photographer, his work, and Malian material culture.

Credits

Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens is organized by guest curator Catherine E. McKinley with Imani Williford, Curatorial Assistant, Photography, Fashion, and Material Culture, Brooklyn Museum.

Significant support is provided by the Leonian Charitable Trust. Generous support is provided by Tom Healy and Fred P. Hochberg and Elizabeth and William Kahane. Additional support is provided by Isabel Stainow Wilcox.

About the Brooklyn Museum

For 200 years, the Brooklyn Museum has been recognized as a trailblazer. Through a vast array of exhibitions, public programs, and community-centered initiatives, it continues to broaden the narratives of art, uplift a multitude of voices, and center creative expression within important dialogues of the day. Housed in a landmark building in the heart of Brooklyn, the Museum is home to an astounding encyclopedic collection of more than 140,000 objects representing cultures worldwide and over 6,000 years of history—from ancient Egyptian masterpieces to significant American works, to groundbreaking installations presented in the only feminist art center of its kind. As one of the oldest and largest art museums in the country, the Brooklyn Museum remains committed to innovation, creating compelling experiences for its communities and celebrating the power of art to inspire awe, conversation, and joy.